Akwesasne Mohawk journalist, author and public speaker Vincent Schilling offers his views on a problematic Kansas City Chiefs history

On January 20, 2020, when the Kansas City Chiefs first battled the San Francisco 49ers in the Superbowl, I shared a series of tweets expressing my opinion as a former sports editor and as a Native American journalist.

In the thread, I explain that the Kansas City Chiefs did not get their name from a Native American, but rather a non-Native businessman and former Kansas City mayor, H. Roe Bartle, who founded a Boy Scout “Indian tribe” organization that taught “Indian values” at away from home camps.

The Mic-O-Say was founded in 1925 under the leadership of Harold Roe Bartle, a former Scouting leader for the non-Native organization, the Cheyenne Council of Boy Scouts in Casper, Wyoming.

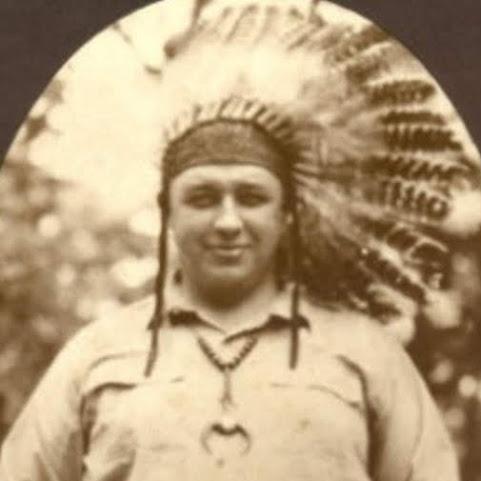

Bartle, who claimed he was inducted into a local tribe of the Arapaho people (which the Arapaho have refuted), was also given the name Chief Lone Bear by an Arapaho chief, according to a Boy Scout “Mic-O-Say legend.”

Bartle often wore a headdress and went by the nickname chief in social circles. When the Dallas Texans football team was looking for a new home, Bartle invited Lamar Hunt, owner of the Dallas Texans, to Kansas City, and the team eventually became the Chiefs, named after Bartle.

The Kansas City Chiefs got their name from a non-Native man who liked to play Indian.

How the Kansas City Chiefs Got Their Name

For further reading in Native Viewpoint: How the Kansas City Chiefs got their name

As I expected, I got a lot of heat for my opinions. The tweet had received over 10,000 likes and 4,700 retweets in a few days, but of course, the most fun was the 1,600 replies. (I think the numbers were possibly reduced after Elon took over X, because they are different now.)

In the series of tweets, I asked people to respect my views. I also complimented the athletes for reaching their levels of athletic prowess and more. But I also stated how the stereotypes portrayed are harmful and problematic.

Though I may compliment the players, I am not going to hold back in calling out the heads of the NFL who ignore harmful behavior. To roughly quote a friend, “Being complicit is accepting the behavior.”

Specifically, I wrote, “I am waiting to see championship behavior from the world of sports in terms of respecting Native culture.”

I have asked myself too many times, how can Roger Gooddell, as the head of the NFL, sit idly by and watch these horrendous stereotypes be portrayed? How could executives at the Kansas City Chiefs Arrowhead Stadium, in any way, shape or form, allow the Tomahawk Chop?

We talk about champions in sports. We talk about championship behaviors, taking a stand for your team, and sometimes winning when faced with insurmountable odds, but are we too afraid to offend our fans that we allow a race of people to be stereotyped?

A real champion stands up to the opposition when they know it is the right thing to do.

The right thing to do is to absolutely not allow stereotypical behaviors into stadiums. The Tomahawk Chop should never be allowed, nor should stereotypical face paint, fake “Indian” costume adornments or anything of that nature.

I am realistic. I don’t expect the Chiefs to change their name anytime too soon. But I would implore them to stop allowing something such as a headdress or the tomahawk chop at games. I don’t see this as an easy task either. As CEO and Chairman of the Chiefs, Clark Hunt once appeared on his wife’s Instagram with a fake headdress, proud of the fact he was once elected “Cherokee Chief” of his Christian camp. They are standing with their son, so I won’t post the image.

But no matter how much I write, no matter how much proof I provide that Native mascots hurt Native youth, who suffer from the highest rates of teen suicide in the nation, people will still tell me to get over it. People will continue to tell me that “they are honoring me” with their costumes, the Chiefs — or any other Native-named sports team — and that I am lucky I am even talked about at all.

If you think you are honoring me. Let me explain why you are not.

In my tweets, I spoke of my Mohawk grandmother, who spoke fluent Mohawk before she ever knew English.

I wrote: “But I think of my grandmother, who was so afraid to be Mohawk, she never uttered a word in her language to me. Lest I also be stolen away to boarding school. I only ask for respect.”

When my grandmother was a little girl, she and her sister were forced into a residential school. My great-grandmother was told by the nuns that she must get a job before she could have her children back. At the school, my grandmother suffered horrible abuse. She never talked about it. Due to her silence, I don’t know the school or where it was.

When my great-grandmother returned with a job, the nuns said things had changed; her daughters had been signed over, and she could not have them back. My great-grandmother resisted and came back in the dead of night. She had to take her own daughters back.

Such a story fills me with real honor.

My great-grandmother went against the opposition to do what was right.

But the story doesn’t have a happy ending. My grandmother lived in a horrendous fear of being a Mohawk woman. Being Native was dangerous. When she came of age to have children, she fled in fear to California. When I was born, my grandmother watched over me for the formative years of my childhood. But because she was afraid, she never shared her fluent Mohawk language with me. She never shared our Mohawk songs or traditions she knew. She did sing to me, but the songs were all in English.

She was desperately afraid I would be labeled an Indian child, and thus, I might be taken against her will to a boarding school.

So, in contrast, my grandmother was too afraid to be a Mohawk. Too afraid to be an Indian; I have people telling me that they are honoring me by doing the things they do at a Chiefs game. They say, ‘Get over it’ or ‘My relative or neighbor is Native American, and they like it.’

So I will say that I find what my great-grandmother did, risking everything to save her daughter, as something that honors me. That is the warrior blood in my veins.

If you want to compare a fake headdress to that same honor, I question your outlook.

I cringe at the Tomahawk Chop, knowing my grandmother struggled to survive as a child amidst a non-Native culture that wanted her to disappear so they could have the land. Native songs are beautiful and mean so much more than who wins a football game. Please think about this next time you want to chop your hand in the air and sing something made up by a PR person.

On a parting note, I really do wish the champions well. I can’t imagine the years and years of hard physical work and training they must have endured to reach these peaks of their athleticism.

Please know, dear champions, I do not wish ill; I wish you the best of lives, with love and friendship within your families and friends.

I say all of these things with a shared desire to have the best for all of our children and to simply, make this world a better place.

We are all in this together.

Vincent Schilling, Akwesasne Mohawk, is the founder and editor of Native Viewpoint. With nearly 20 years of experience as a Native journalist and former member of the White House Press Pool, Vincent works to uplift underrepresented voices in the world of media and beyond. Follow Vincent on YouTube.com/VinceSchilling, on Twitter at @VinceSchilling or on any other of his social media accounts by clicking on any of the icons below.

Support Native Viewpoint a Native multimedia website, by clicking here.